Last May, when I learned I had a malevolent disease, one frightening thought kept floating back into my head: "gosh, this thing may kill me." But after a while, my fearful reaction surprised me. Of course, we all die. So what exactly made this news different? It was my assumption I would live long - to a 120 years specifically. One fact, one assumption and one aspiration had created more than an assumption, it had morphed into an unstated, firmly held belief.

- Fact: I was 40 when Paul was born.

- Assumption: Paul would probably be 40 before he had his first child if he is anything like myself.

- Aspiration: I would like to see how my grandkids turn out, meaning grown adults, in their 30s or 40s.

- Fact + Assumption + Aspiration = 40 + 40 + 40 = 120. Funny how the brain works, no? Over time, I had mulled over this whimsy so many times it become a truth. Hitler is attributed with the idea that if you say a lie 10 times, it's still a lie; say it 100 times and it becomes a fact. I had concocted a fact.

But now, damnation, the lymphoma was akin to a freight train that had plowed right through my flimsy logic. For me, it raised the question of two paths - did I want a long life, or a richly lived one? My answer - - the latter.

So if it's a vibrant existence, next was to assess how had things gone for far? For that, I leaned on a mantra by Father Tom Belleque, a deeply gifted priest who used to lead the parish I attend. "We should give thanks for the treasures, time and talents afforded to us." Over the years, I had pondered his tenet a thousand times and concluded that this, to use the parlance of my consulting friends, is a classic "mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive" statement of all the good things in life.

- Treasures: Things handed to us without us needing to earn them, like great parents & siblings, good health, and whimsical, caring friends.

- Time: Rewarding, non-trivial, experiences by which your world views grew deeper, sturdier, happier and broader. These include adventures that may have been painful at the time.

- Talents: Instances where you've taken strengths or passions and honed them further.

The Exercise

It was time to dig into this by way of a simple exercise, which in my case I undertook across several morning walks.

- Make a list of your Treasures, Time and Talents.

- Make a list of your setbacks. )REAL setbacks too, items on the scale of getting mom and dad as my parents. I could not include trivialities like bad rush hour traffic, too many stops on my elevator, etc. )

- Compare the two lists.

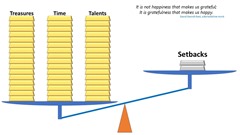

What did I find? Gosh, my list of goodness was very, very long. And guess what, I had just two BIG setbacks - a failed marriage and lymphoma.

Life is Epic: Comparing Goodness to Setbacks

Abe Pachikara, Copyright 2017 (click for larger image)

Discoveries

Without question, my life resides much more in the epic end of the spectrum. True, I had yet to earn a Nobel, a MacArthur Fellowship, make my first million, etc., etc. but 4 discoveries came into view that changed how I dealt with my lymphoma.

- Discovery #1: The tally was not even close. I kept visualizing this old fashioned scale, tipped deeply to one side. My setbacks were a rounding error compared to the sheer weight of all the goodness in my life.

- Discovery #2: I had "arrived" a long while ago. Another shocker - - already, my goal of a good life had been accomplished. I know I want more, but I could hardly complain.

- Discovery #3: My gratitude fell far short, dismayingly so. I had to look at my God and wonder how I had missed this, all these years. And I had really never said enough thanks. In my mind's eye, I saw a child who gets so many toys, he just shrugs his shoulders, says "thanks" half-heartedly and walks off. It was an embarrassment of riches.

- Discovery #4: In truth the lymphoma was "too late." If it killed me now, certainly that would suck, but I had been granted so much goodness.

Implications

Together, these four insights had a strange effect upon myself (and I think would similarly galvanize any mortal): a celestial Teflon coating surrounded me. Certainly, the cancer was bad, and undoubtedly, the treatment would be non-trivial, but neither was all encompassing. Both were finite, and neither could take back all the goodness afforded to me. I entered into the treatment with a different perspective that I had expected.

So this raises a notion to share - a deep sense of gratitude re-frames many things. I think everyone should undertake this "Life is Epic" exercise. Certainly for many, their existence on Earth is very, very hard. By no means is my intent to trivialize this. Rather, I don't think as humans we have a full view of the goodness in our lives. Such self-awareness can only benefit each of us.

Again, Some Refined Goodness

In closing, the words of David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk, come to mind:

It is not happiness that makes us grateful,

It is gratefulness that makes us happy.

No comments:

Post a Comment